Diversity Claims Meet Data

Our analysis of 15 years of data from the largest registry of clinical studies shows that the data lags behind the rhetoric.

Diversity is a topic which has been a lightning rod for negative press recently. So much so (in fear of retribution) universities across the nation choose to dismantle their DEI offices, rename the titles of those who were supposed to lead these efforts, and an array of other choices. In my view, these are not necessarily cowardly choice, but choices made with the intent of preserving the institutions from shutting their doors. Many institutions in 2020 heard the call for a deeper reckoning with the racial inequities that are not only a foundational part of the United States, but also the institutions themself. Now there is a call for that reckoning with the past and present harms to stop, and the people brought in these places are told to pretend these inequities do not matter. Many should rightfully be disheartened by this, but at the same time a lot of places touted DEI principles without a clear path to sustained change.

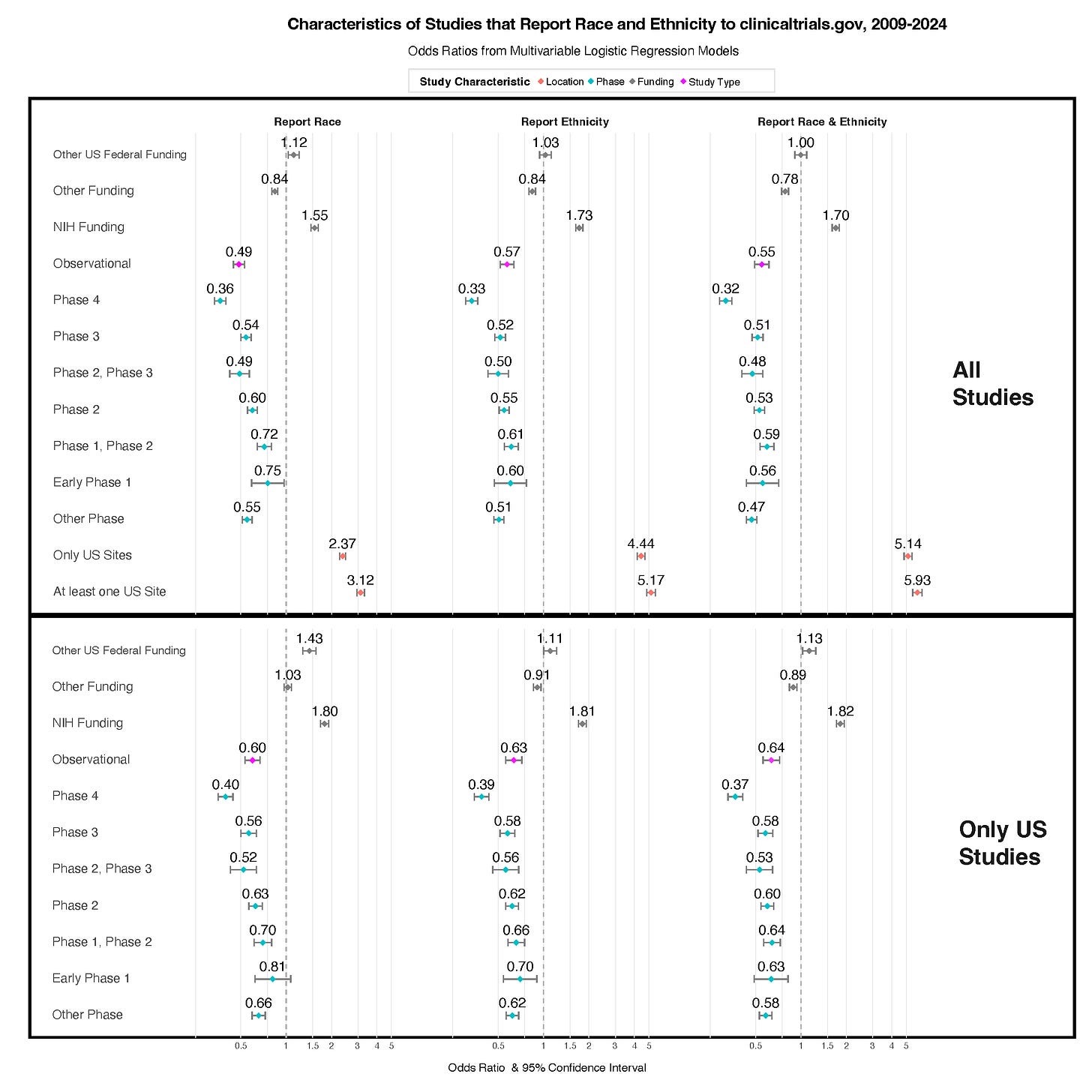

DEI programs and other inclusion initiatives were dismantled swiftly due to a lack of genuine support. In contrast, work that is truly deemed mission-critical is not easily dissolved. As a researcher, I feel it is my duty to provide evidence for what happens in the world. If there’s a backlash against DEI, particularly if people claim that it’s not important or that our objectives have been achieved, I would like to see the evidence to support those assertions. I am a senior author on a pre-print that evaluates reporting of race and ethnicity and the diversity of study participants using data from the largest registry of clinical trials. Our main finding was that most clinical studies and trials do not report the race and ethnicity of participants to the registry. Reporting to this space would facilitate easier evaluation of diversity. If DEI was truly important, why would over half the studies not report the race, ethnicity, and other sociodemographic factors to the registry?

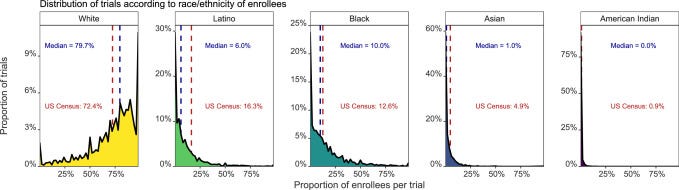

A similar analysis was published in 2022 in The Lancet Regional Health: Americas examining US-based interventional clinical trials registered through 2020. These trials are foundational evidence for evaluation of safety and efficacy for drugs that are commercially available. The racial categories in this paper were aligned with the US Census and Department of Health and Services Guidelines. In this analysis they found that US-based drug trials also lagged representation of all racial and ethnic minority groups compared to their proportions in the 2010 Census as shown in the figure below.

In our pre-print, we used the NIH Office of Management and Budget Race and Ethnicity Categories. Clinicaltrials.gov is managed by the National Library of Medicine. Given the significant reductions in the US federal healthcare workforce, monitoring this data could influence the willingness of sponsors to report or potentially even what can be reported without fear of persecution. Nevertheless, our pre-print is an analysis from 2009 to 2024 data and offers a perspective on an evolving environment. It can serve as a comparative example after the on-going dramatic disinvestment in federal research support and infrastructure in the United States in 2025.1-4

We conducted this analysis with the initial intent to assess the current state of racial and ethnic diversity in clinical research. Complete reporting of participant race and ethnicity is necessary to accurately interpret diversity. The national and social context of these results must always be presented when interpreting race and ethnicity. While completeness of data is important, ensuring that appropriate context is provided for results is equally important, given the potential consequences of misinterpretation. Among studies registered clinicaltrials.gov we have knowledge of well over 70% of studies with reported results. The way that those categories are reported and timeliness of reporting can all be improved. As this project continues, I am excited to provide evidence to assess assertions about who is involved in clinical research.

There should be concerns about the maintenance of this registry. In this July 2025 correspondence piece in The Lancet, the authors documented evidence of manipulation of US Federal Government health-related data. This past Friday after a below expectations jobs report, the White House fired the labor official primarily responsible for this report. Selection bias occurs when the data we analyze do not reflect the people we claim to study, and efforts to track diversity in research exist to address this problem. The most flagrant form of selection bias happens when investigators suppress or highlight results simply because they fit their agenda; withholding race and ethnicity data leaves us unable to see who is involved in research and makes conclusions less trustworthy.

This problem is not just theoretical, recent reporting at STAT shows it unfolding in real time at the highest levels of U.S. biomedical research. In this article they overview how the current NIH Director has a career where he has touted his work studying vulnerable populations and health disparities. Now under the well-documented unraveling of health disparities research at the NIH (which is being conducted under the false guise of calling it DEI/diversity science despite the documented unequal prevalence and prognosis of diseases) an environment has been created where researchers and institutions are incredibly hesitant to confront the role that race plays in documenting and evaluating disease burden. One thing I am certain of, despite the lack of willingness to acknowledge that race and other socially constructed concepts matter for the prevalence and prognosis of suffering, unequal suffering will persist without solutions that acknowledge lived experiences. Telling people that their experiences and identities do not matter will not make them irrelevant.

References:

1. Cutler DM, Glaeser E. Cutting the NIH—The $8 Trillion Health Care Catastrophe. JAMA Health Forum. 2025;6(5):e252791-e252791. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2025.2791

2. Sommers BD. The Public Health Damage—and Personal Toll—of Federal Worker Layoffs. JAMA Health Forum. 2025;6(5):e252652-e252652. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2025.2652

3. Galea S. The Potential Consequences of Disinvestment in Health in the US. JAMA Health Forum. 2025;6(4):e250803-e250803. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2025.0803

4. Sinclair AH, Harris MJ, Andris C, et al. NIH indirect cost cuts will affect the economy and employment. Nature Human Behaviour. 2025/06/02 2025;doi:10.1038/s41562-025-02238-x