Handling Chaos and Uncertainty

Some thoughts on the unsettling actions and vibes that early career researchers in the scientific community are experiencing.

Uncertainty is the name of the game right now sadly. For me and many others at the early stages of what we hope will be a meaningful career, it feels overwhelming. Good planners know that success takes understanding the downside, minimizing risk through our choices, and a bit of luck. But for those of us building our careers in health sciences, the “luck” factor seems especially fragile these days. We are confronting the possibility that being unlucky might become one of our biggest headwinds.

Context: This was written and published on February 14th, 2025, at 7:30 a.m. Eastern Time. Considering every day, we are getting some new fun onslaught on the scientific process; I figured it was relevant to document the headspace I was in when writing.

Take the Diversity F31 supplements as an example from my field. These awards require extensive applications (often upwards of 50 pages of materials) and go through the same grading process as the non-Diversity F31 awards. The NIH F31 Fellowship is one of the largest awards available for biomedical doctoral students, providing significant financial support throughout the PhD and signaling a candidate’s potential to secure future funding, which is increasingly critical for a career in health sciences research in academia. The “diversity” mechanism of this fellowship not only supports a firm foundation in research methods and mentorship but also actively broadens the pipeline of scientists from diverse backgrounds. Recently, however, grants submitted months in advance were pulled from the study sections that evaluate them, right alongside the non-Diversity F31s. For many early-career researchers, this was the only opportunity to secure NIH funding to support their work (the timing in your degree where you both have enough experience to assemble this award application while also having enough time in your program left to benefit from the support is fairly narrow usually only a couple year window in 4-6 year degree programs). As of this writing, these applicants have not been given a chance to pivot their hard work to another NIH mechanism. They simply lost their shot without so much as a review. More reporting is here by Usha Lee McFarling and Anil Oza.

Update: Some study sections reportedly have reentered Diversity F31 applications into the general pool, but the official guidance on what is happening remains murky. Many institutions have responded with frustrating passivity, offering little in the way of advocacy or legal challenge.

This frustrated many people, but few institutions made a large effort to combat this. People who are promising scholars but the most vulnerable in the institutions were hung out to dry, and there was a lack of quick legal challenges.

Esther Choo (an emergency medicine physician, health policy researcher and founding member of Equity Quotient) captured this concern perfectly in a recent BMJ opinion piece speaking to the backlash against research focusing on subgroup differences, which I believe has major parallels to the limitations of not ensuring that there is support for vulnerable groups in scientific training.

She concluded:

“Whatever the new administration intends, stifling our ability to identify and understand specific groups does not make the groups go away. It simply makes our science less insightful and robust. Striking terms like those mentioned above hampers our ability to understand our whole population, in all its inherent heterogeneity, to identify and address when and where existing structures, systems, and therapies are not adequate to ensure health. That is harmful to those already at risk for poor health outcomes; it’s harmful for us all as an interconnected body of people. And sustaining barriers to entering research fields keeps us from our own full potential as a nation of scientific discovery.”

The ideas of people from different backgrounds than the fairly homogeneous scientific training pool are needed. Some of the biggest impact happens at the executive C-suite level and top university leadership positions, and across the nation in biomedical research there is still a striking lack of diversity at these levels. Stifling training now will make sure that this reality remains.

As if that were not enough, the NIH also announced unilateral cuts to indirect funds Friday February 7th: NOT-OD-25-068

Update: These cuts were swiftly met with legal challenges from multiple states and institutions. As of now, the action is considered illegal, but it’s worth monitoring to see if it’s appealed to higher courts or if there are attempts to enact it with other future legislative actions. The STAT News Team has done a great job covering this here by Jonathan Wosen and Angus Chen

I won’t go into the specifics in this post, others have explained it in depth far better than I would, such as Delip Rao here and a fellow Duke colleague, Don Taylor here. The short story is that cutting indirect funds at this scale will devastate biomedical research in the U.S.

Early-career researchers have already felt the sting of these policy changes on a small scale (through their fellowship applications being in an unclear status). Now, the entire field is experiencing a similar shock in the macro sense. There’s been extensive discussions about the need to communicate the value of scientific research more effectively. That has become even more urgent as we lose ground to mounting policy setbacks.

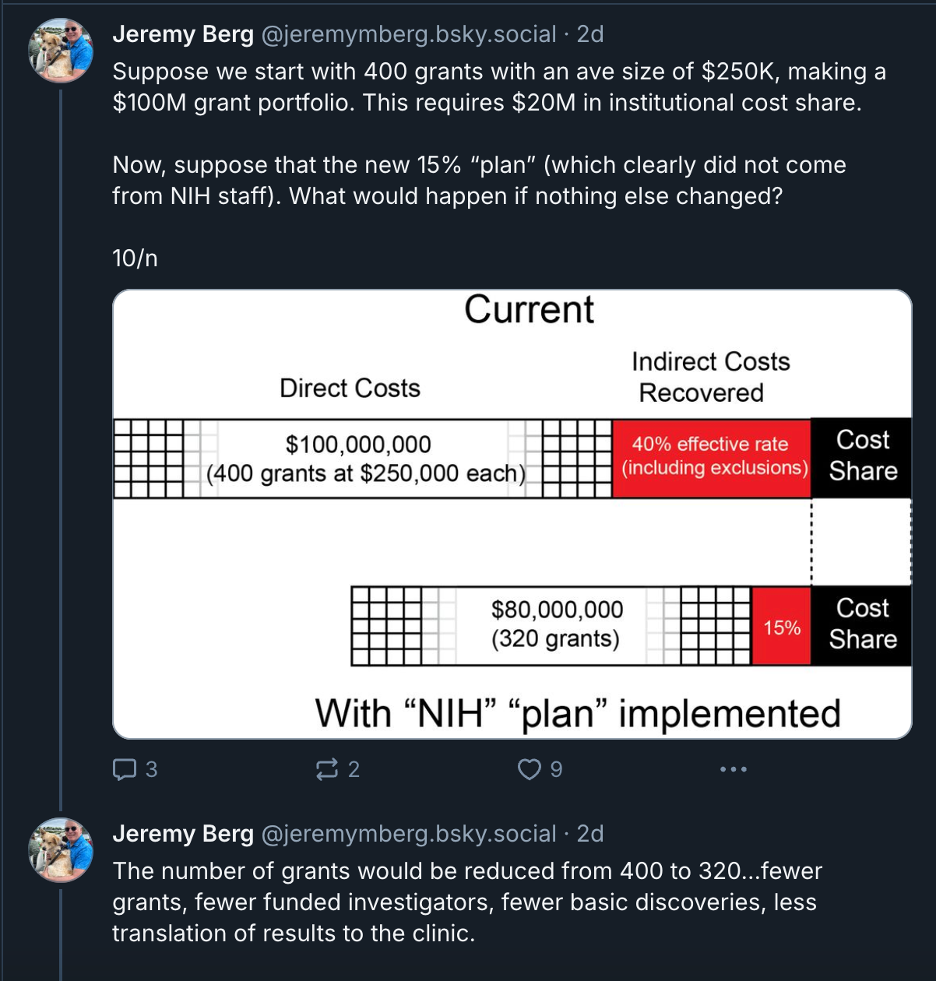

Jeremy Berg (associate senior vice chancellor for science strategy and planning, health sciences, and professor of computational and systems biology in Pitt’s School of Medicine) provided an interesting thought exercise of what an emergency plan to combat this action could look like in a recent BlueSky thread, explaining how institutions could respond to slashed overhead by raising funds in other ways:

Here is how the plan to slash indirects would have looked if immediately implemented for a full year under a round number of $100,000,000.

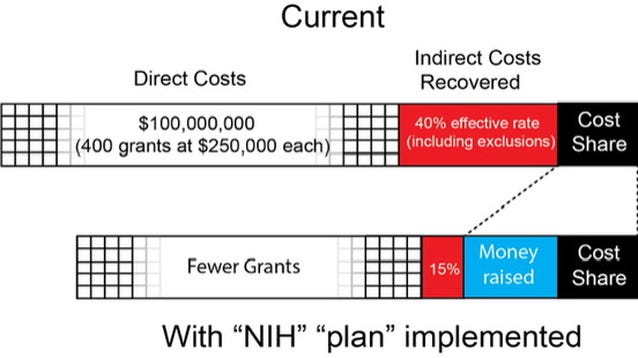

In these next two images he overviews how money raised can help a short shock to the system like was proposed.

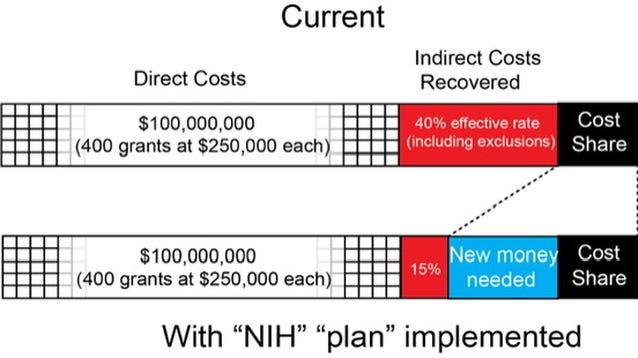

And in this one it corresponds to what maintaining the status quo would look like:

Institutions can pivot, but pivoting in this case without the ability to plan a dramatically different view on how to support biomedical research will have negative cascading effects that by the time they are felt, it will be too late to reverse the damage.

This new perspective on biomedical research from the current administration dramatically eats away at the lead we have in the US. I anticipate that the divide we currently have, where the institutions with the best lawyers, most resources, and most prestige will continue to fight for their positioning and science will continue (at a smaller scale). People will continue to push to be at these places, and opportunities for advancement will be even slimmer than before. Many institutions might shutter their doors altogether, and/or cancel training programs. Science is already an exclusive career where people work and develop ideas and trade off some of the earning potential and simplicity of a job in a non-academic environment to pursue the chance for intellectual freedom in an academic environment. Again, thinking of the early career colleagues I have, over the coming weeks and months more people than ever will ask themselves “Why bother?”.

However, this is not just a problem for academics; it has real implications for public health and medical innovation. Local economies can suffer, since much of this research underpins jobs at hospitals, universities, and biotech startups. In other words, when we fail to invest in science, we end up losing not just the next generation of discoveries, but also the people who innovate and the local environment that is a product of science.

So, what can you do if you are not directly involved in the NIH ecosystem? First, it’s important to stay informed. By following credible news outlets, scientific journals, and community voices, you will get a clearer sense of how research funding impacts healthcare, local economies, and our broader scientific progress. Another practical step is to support science communication efforts. Whether through sharing articles, podcasts, or videos, spreading accessible explanations of why science funding is important can go a long way toward building public momentum. You can also contribute locally. Many nonprofits, labs, and university programs rely on philanthropy, volunteer work, and even a simple retweet or Instagram post to help spread their mission.

Despite all this chaos, I am holding on to a primary source of optimism: the resilience of the scientific community. If we pull together, communicate our value clearly, and keep fighting these regressive policies, we can make room for fresh voices and new ideas. Right now, I am just trying to capture my own thoughts and uncertainty, in hopes of keeping myself and others engaged.