The work must go on

Now it is easy to feel frozen, the future does not feel guaranteed, but we also do not know what it holds.

Today I turned 26, which is known in the United States as the age that you can no longer be covered for medical expenses through your parent’s health insurance. I am fortunate enough to have health insurance through my Ph.D. program, but having a job that has benefits or making enough income to pay for an insurance plan out of pocket is not lost on me as a future consideration for the ever-changing stage of early adulthood in the US. Either that or I can choose to never need healthcare again. This would be great, but based on the status of our system now, highly unlikely. Year 4 of my Ph.D. program has officially ended, and I am now a rising 5th year Ph.D. candidate entering my final year (hopefully). This current moment is not considered stable in science, medical research, and especially my focus area in health equity research. Even as I navigate this new kind of chaos in the last year of my Ph.D. journey, I have found myself thinking about how I move forward in this moment instead of being frozen in place. I applied to pursue a Ph.D. in Population Health Sciences as a bright eyed 21-year-old undergraduate student who hoped to change the healthcare system. Many people get this far into their Ph.D. journey and become disillusioned by the headwinds and trials they face. I certainly feel more aware of what I do not know and the limitations of what is in my control at this time. We need to see a return on the investment of time and resources that have been poured into me and other trainees. That return on investment requires a level of research integrity, responsibility, and mental fortitude that is challenging in this moment. Academic research is abruptly losing a lot of the massive financial support that the United States federal government has provided for decades.

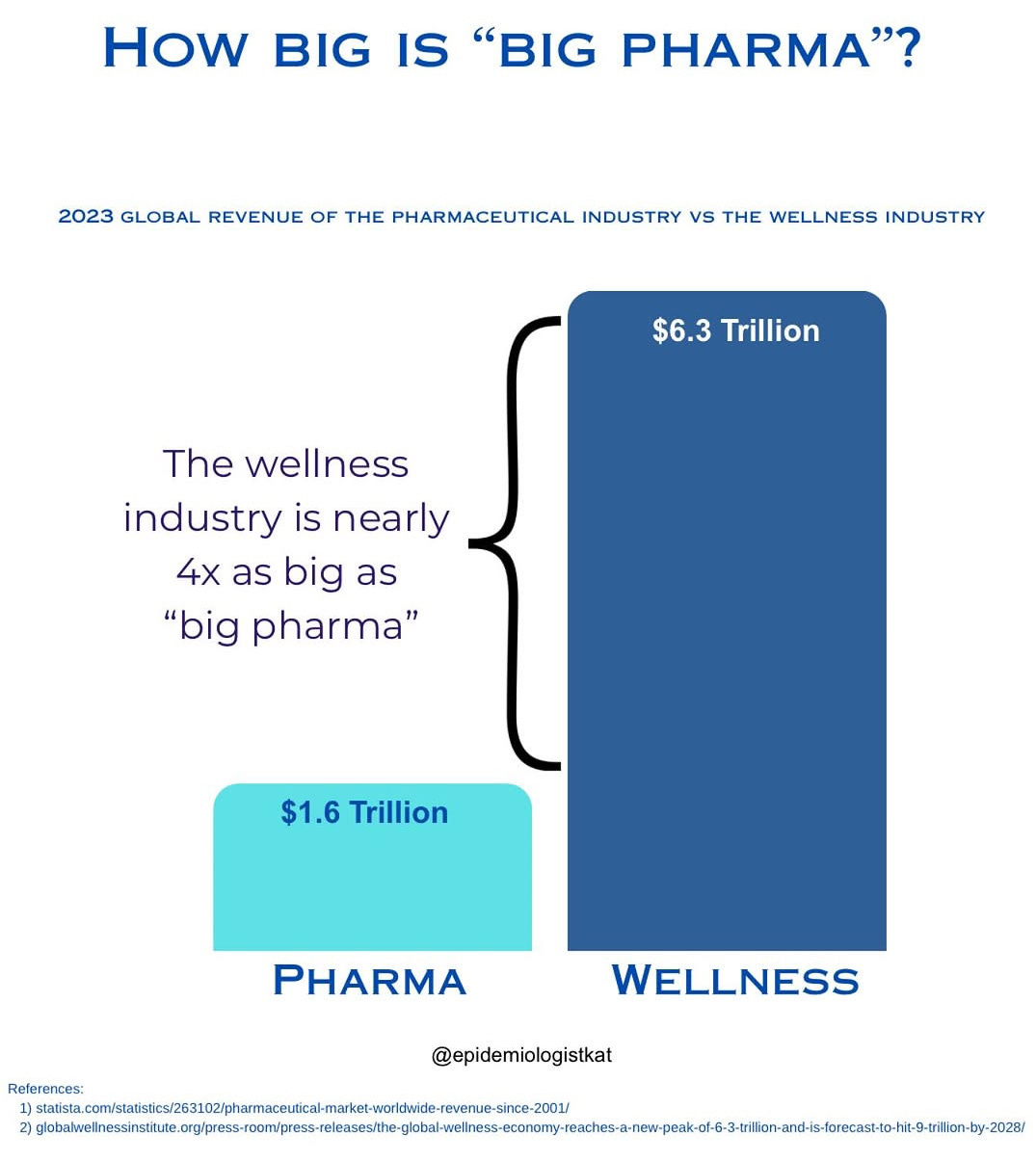

I applied to my Ph.D. program in 2020 during the apex of the response to a once-in-a-century global pandemic. For everyone in healthcare, it was a formative (and traumatic) time. In broader society, everyone was forced to learn about our healthcare system either through loss, disruption, change in routine, or all of them combined. Entering my first year of my Ph.D., I hoped that the importance of healthcare would be seen through the vast loss of life and disruption globally. In many ways, the importance of healthcare was highlighted, but that highlighting provided the opportunity for people to emphasize failures and promote different methods for change. Many of these different methods were not evidence based, but were still gaining prominence through new medical officials’ communications. This figure by Katrine Wallace, Ph.D. (Dr. Kat), an epidemiologist at the University of Illinois at Chicago, demonstrates that revenue of the wellness industry is far greater than pharmaceuticals.

There have been many people who cry out asking for more wellness remedies to fix our nation’s health issues, citing the amount we spend on pharmaceuticals and treatment opposed to disease prevention. I understand that cry. Drugs are complex, as are the processes for testing, approval, distribution, administration, acquisition, and taking them. But we DO spend a ton nationally on wellness. Increased spending on wellness, without supporting safety and monitoring, (and uplifting researchers who can investigate if health is improving) will create an environment where there is even more dramatic loss in our nation’s health progress. Make no mistake, our healthcare system right now centers on treatment opposed to prevention. That is a problem. I believe to fix this problem we must prioritize population health centered approaches that involve collective action opposed to individualism. I prefer an environment that requires evidence-based plans, as opposed to hoping for the best. Those plans take resources and knowledge that is not available quickly or cheaply, and burying our heads in the sand hoping for the best will not protect us.

One of the many reasons people seek out alternatives to our traditional medical options are because of the inability and/or unwillingness for experts to communicate with people in an accessible manner. I have greatly appreciate the work of Dr. Robert Califf, a former FDA commissioner whom has been very vocal about the implications of unraveling of the scientific environment. He’s spent his entire career trying to make progress in through his social media and the news outlets to promote accessibility of information. Lizzy Lawrence, an FDA Reporter at STAT News highlighted a presentation Dr. Califf had at STAT’s Breakthrough Summit West. Dr. Califf stated,

“I don’t know how the policies are going to be enacted in the right way without the people to actually do the work that it takes to get it right”

The voices of all scientists from trainees to advanced investigators like Dr. Califf are incredibly important right now.I also commend his willingness to start his own personal blog titled “Califf’s Commentary” his first post is here.

In this moment, we have an unraveling of biomedical research infrastructure that not only is impacting my own training and research ability, but the future of scientific research. Many of the conversations I’ve had recently are about pivoting research focus. If I could go back into the future to newly admitted Ph.D. student Michael Green, the most straight forward advice would be to pursue something “non-controversial” so he could position himself for a career to pursue science that the current administration deems “non-controversial”. Avoiding controversy is not why I decided to pursue a Ph.D. in Population Health Sciences focusing on how people are socially treated in health systems. The definition of controversy is also constantly changing, so if avoiding controversy is your guiding framework, your target will be very unstable.

I am pursuing this path because I have lived experience where my family members suffered because they feel like they were mistreated and/or unwelcome in healthcare spaces. In this moment, their experiences and trust in health systems are even more fractured than before. Simply pivoting from that work would not help them, so I cannot pivot from the greater mission, given that mission is core to my identity. Science is centered on controversy, we ask questions, run experiments, and make claims based on those experiments. Despite the pivot in how we support (or choose not to support) healthcare research, since I believe the new chaos will not work, we still need people in place to propose new solutions. I am concerned about people who hap-hazardously pivot from their alleged principles. At the same time I understand that the compensation you get in academia is well under corresponding positions in industry or another field. If the mission driven nature of academia is lost, and your ability to choose what you pursue based on your principles is lost, weathering the storm is a lot easier in places where you will make far more money or have less conflict. Hopefully people who are fighting for change are able to weather this storm, but sustaining yourself not only takes financial resources, but also mental fortitude.

Making big decisions in moments of crisis is hard. That’s why I really try to work on my relationships during times when there is not crisis so that I hopefully have a firm floor of support. In past 4 years of my Ph.D. program, I’ve had my host of swings in my family life, romantic life, friendships, professional life, all with the full range of wins and losses in all those areas. Even with these swings my abilities have objectively grown; I entered my program with a single peer-reviewed article, and at the time of writing this I have 19 total articles that have been published or are under review. This is accompanied by a research portfolio supported through an ~$90,000 NIH diversity supplement grant and ~$90,000 through a NIH fellowship grant. I have no papers in “top-tier” high-impact factor journals, but I by no means think that my experience and training has been unsuccessful. In academia there is always more to grasp for, it would be cool to get another grant, it would be cool to have double the number of papers I have now, it would be cool to start a company, it would be cool to get a faculty offer straight out of my program in my dream city, and, and, and, and…

There will always be a new achievement to fixate on, but the path to that achievement is not always dependent purely on effort. We all get lucky, and successful people at the training stage often have a support system that provides a floor for many opportunities that lead to success. Some people will be put into positions to succeed because they were in the right place at the right time. At the same time, some people are extremely talented but are shunned. I recently read the new book “Abundance”. In a section on scientific innovation by Derek Thompson from the Atlantic. He highlights how the technology for the COVID-19 vaccine, a mRNA vaccine, was a technology that never received federal funding and led to Katalin Karikó one of the scientists who pioneered it to eventually being pushed out of academia until some scientists indicated interest in her work at a biotech company called Moderna around 2013. She eventually won the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, alongside Drew Weissman, for this technology. Having decades of feeling like a failure are not a part of my path right now, but in science many of the most innovative careers and ideas have come from getting little to no real gratification for major parts of their career.

Many people might look at my life up to year 26 and say they wish to have what I have. At the same time, many believe I am someone who simply got lucky because of the opportunities and fortunes I have been put into because of a stellar mentor team, “name-brand” educational opportunities, and few external obligations like a family or large financial liabilities. I hope to approach my career with a level of awareness of what I have been granted through luck and skill, all while acknowledging that many of the key components of life surround both. In this moment it feels clear to me that the health equity centered research I want to pursue is going to be more challenged. The NIH, NSF, and other US federal research funders already had challenges where it favored feasible research and universities with a history of receiving grants. Even with these challenges, an area it was a global leader in and had immediate impact on lives was by facilitating a ton of advanced scientific training. There might be ways to supplement the lack of project centered research dollars though foundations, industry, and other areas. However, scientific training has been facilitated through a consistent investment from the government at a scale that not only will be hard to replicate, but it losing it will have a chilling effect on the amount of collaborators and people I can work with in the future.

Despite these headwinds, I reflect on this 26th birthday and declare that the work must go on. The moments I experience big scientific “wins”: a paper at a journal getting accepted, getting into a program, getting to speak places, getting grants - all have meaning for my CV and my career trajectory. However, the day-to-day activities are still mundane. There certainly might be less of those wins in the near term, but even when that success comes, the process is more rewarding than the outputs. I find myself reflecting on the great relationships and people that I have met along my journey. Cheers to 26, hopefully I can stay healthy in the face of a ton of actions that will also make that more challenging!